Biased reporting is much in our minds at the moment, where there is often the suspicion that wild invention is being used to change our behaviour through fear and misdirection. Here at the American Museum we have eye-catching evidence that tall tales and exaggeration are in fact nothing new – even in what one might presume was a truthful document. Several of the maps in our historic collection betray their creators’ doubtful intentions when looked at in a modern light.

For sailors, a map was for the practical purpose of travelling from one shore to another. They had their charts, or ‘portolans’, which impress today’s observers with their accuracy and detail. For non-seafaring people of the fifteenth and sixteenth century, maps had other purposes. Some mapmakers placed Jerusalem at the centre of the world and were mainly concerned with representing significant events in bible history. Others though, used maps to inspire curiosity, often mixed with fear, about strange lands and their inhabitants, serving the same desire for entertainment and speculation as science fiction nowadays. These maps were filled with monsters and dreadful beasts designed to instil in their viewers, awe and unease of these strange and distant lands. Some of the monsters depicted were pure invention, others arose from misinterpretations of foreign customs and modes of dress. In those days knowledge of the world was severely limited and the imagination of the map maker had a wide scope.

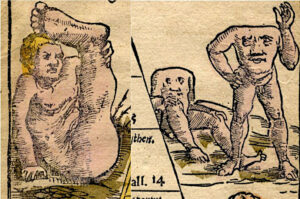

A craving for the bizarre and the fantastic seems to have been a feature of medieval life. Beset by hardship, plague and war, the depiction of monstrous races of men with distorted features sometimes sprang from a morbid curiosity about deformity and disease.

The Nuremberg Chronicle, published in 1493, was one of the most remarkable books of its time. The illustrations around one map include a six-armed man and a woman covered in hair.

Nuremberg Chronicle – Hairy Woman and Six-Armed Man

Two further examples of foreign oddities come from Sebastian Munster’s Map of Asia, from 1545. The famous Sciopods, or ’shadyfeet’ people, whose enormous feet served as a shelter from the sun were probably an over-extrapolation from rare cases of people suffering from elephantiasis. The same map features the Acephali, or headless creatures, whose faces appear on their chests. Usually depicted in Libya in several old maps, this is very likely to have been a misunderstanding of the cultural dress of the burnoose-wearing desert nomads.

Sebastian Munster – Map of Asia – Sciopod and Acephali

It should be noted that it wasn’t only maps making such strange claims about the people of foreign lands. Reporting of strange races has a long history in Western literature, for example, Herodotus in the fifth century BC writes of dog-headed men and ‘others having no tongue or nostrils’, probably indicating the use of masks.

Possibly the pinnacle of the monster maps is Sebastian Munster’s woodcut illustration, Mostri marini & terrestri from his Geographia, printed in 1550. Munster took his inspiration from the bizarre creatures depicted in a 1539 travelogue by Swedish scholar and cleric, Olaus Magnus. Because of its vivid colours and lively execution, Munster’s work is considered to be the immediate source for illustrations and pictorial embellishments in many later maps whose sea beasts enlivened and terrified generation upon generation of landlubbers.

Sebastian Munster – Mostri marini & terrestri

The creatures along the top border of Munster’s illustration are in fact animals from the Far North, but one bear-like animal gives pause for thought. ‘This creature is an insatiable glutton. By squeezing itself between trees it empties its belly and then rushes back to continue eating. … those that wear the skin sometimes become like the animal.’

Munster’s ocean is crowded with sea creatures of monstrous appearance. There is the twin-spouted ‘Fish of the Devil’ which may ‘overturn ships unless frightened away by the sound of trumpets, or they may play with empty barrels thrown in the water, a game which amuses them greatly.’ On the print, sailors can be seen frantically casting barrels into the water to distract the beast.

Sebastian Munster – Mostri marini & terrestri

Another annotation states that ‘there are crabs so large and strong they can kill a swimmer…’. If these illustrations are based on mariners’ tales it is a wonder that anyone in those days ever put to sea.

As time passed, such gross exaggerations of man and beast became somewhat tamed. Tastes changed so that, as in the Map of the Northern Regions by Abraham Ortelius (1587) sea creatures became less horrifying and almost ‘dainty’. It is also curious that, as the borders of the known world widened, the monsters on maps were placed in increasingly more distant lands. A case, perhaps, of increasing general knowledge of the world reducing the scope for blatant bias.

The information source for this article is Monsters in Maps, an article written by Anne Armitage in 1995 for America in Britain.

Buy Tickets

Buy Tickets

Previous

Previous

Back to top

Back to top